Is it a fake? Is it photoshopped? Is it real? Paul Hansen’s winner of the 2012 World Press Photo competition is just the latest example of more than 100 years of continuous discussions about the manipulation of photographs.

However, instead of asking only if prize winning images are manipulated (and of course in some way they all are), we should also ask why are they changed to become the way they are? Or, to put it differently: what kinds of photographs win awards? When we look closer at the changing styles of the winning photographs since the beginning of the World Press Photo competition in 1955, we see that Hansen’s picture is part of a cinematic form of expression that has emerged in the last 6–7 years.

The image portrays family members from Gaza carrying the bodies of a two small children to their burial after being killed in an Israeli air strike. It is no coincidence that it has been called a movie poster. However, the photo is more like a still; a story frozen in time, but condensed with motion and movement, inviting us into a narrative of what has happened before, and what might happen next. This new trend is different from other dominant styles among the WPP winners.

Some of the winning pictures hold what we can call news moments (similar to Henri Cartier Bresson’s decisive moments). Most of the news moments are from the 1960s. A prime example is Eddie Adams’ 1968 picture of the execution of a suspected Viet Cong member, showing the exact moment of the bullet’s penetration of the brain. The impact of the picture lies primarily in capturing a certain news event in a fraction a second.

The closer we get to this century, the fewer pictures we see of such news moments. Instead we see more feature-like photographs capturing – not a moment, but a general situation or condition. Take this winner from 2004 portraying a woman mourning a relative after the Asian tsunami of December 2003.

The photo is constructed around a juxtaposition between the dead body, represented by only an arm in the left of the frame, and the bereaved, represented by a woman lying face down on the sand in the right part of the frame. This kind of explicitly artistic visual rhetoric prevailed from 2000–2004.

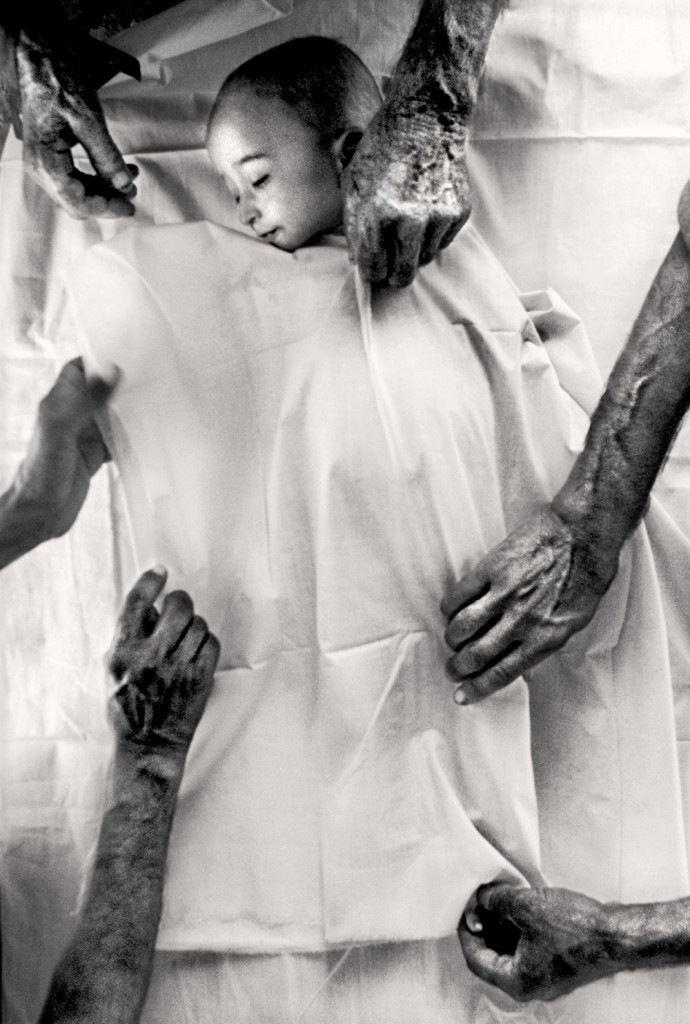

The 2001 winner portrays how the body of a one-year-old boy who died of dehydration is being prepared for burial at Jalozai refugee camp in Pakistan. It is a very rare example of a picture being taken in a full bird’s eye perspective, directly from above.

The picture is dominated by the white color of the draping sheets, covering the body of the little boy, so we only see the left side of his face. He seems at peace, and the picture exudes calmness, giving it an almost ethereal dimension. Combined with the angle of the arms draping the sheets, the picture is more an aesthetic moment than it is a news moment.

Hansen’s picture is neither a news moment nor an aesthetic moment – not to say, of course, that it does not have style. All images do. Instead the aesthetic tendency exhibited in this picture is a more of a kind of movie realism, a sort of photographic cinema verité. We see a similar tendency in the winners from 2007, 2008, and 2009.

The 2007-winner shows a US soldier sinking onto an embankment in a bunker in Afghanistan. The 2008 winner depicts a policeman entering a home in Cleveland, USA, in order to check whether the owners have vacated the premises. In 2009 we see women shouting their dissent from a Tehran rooftop following Iran’s disputed presidential election.

These images are not colorful, there are no close ups, no clear, simple or stylized compositions, and no conspicuous juxtapositions or an obvious use of some part to represent a whole. They give the impression of the fictional realism we sometimes encounter at the cinema.

While the beginning of the decade presented photographs that have their main rhetorical appeal in their compositional and aesthetic organization, these photographs appeal more through story-making. The first kind invites the viewer inside the frame, encouraging exploration of the elements in the visual moment, captivating us through visual design. The second kind invites the viewer outside the frame, encouraging participation in the construction of a narrative, engaging us in speculations of what has happened and what will happen.

This kind of neo-realistic press photography seems to be more open to interpretation than the more obvious symbolic photos. The strange thing, though, is that the more the pictures draw us into a story of mostly our own creation, they seem to draw us away from the events they are depicting. They are all fabulous images, but even when provided with the backstories I remain a spectator immersed in the story, in awe of the artwork, waiting for the movie to premiere.

World Press Photo award-winning photographs by Paul Hansen, Arko Datta, Erik Refner, and (clockwise from the upper left) Tim Hetherington, Paul Hansen, Pietro Masturzo, and Anthony Suau.

This text has previously been published on the site No Caption Needed. If you are interested in photojournalism, don’t miss it.

[…] from the traditional winners over the years that way, however, it seems to also be part of an emerging trend among the winning photographs of recent years: a cinematic aesthetics that combines artistic […]